An in-depth evaluation of revolutionizing the old-school method of surgical care and, in turn, building a better surgeon.

An Editorial by Dr. Mit Desai

Imagine a world where 100-year-old technology remained the standard – not because it was perfected, but at the detriment of progress and outcomes. The phones in our pockets are rarely more than 3 years old, the cars in our driveways seldom more than 10. Yet the design of surgical services is still based on ideas put in place in the late 1800’s.

If you told someone that dozens of patients, admitted to the hospital, would wait half a day or more, to be seen and cared for by their internal medicine doctor so he/she could finish office hours, they would think that was ridiculous. The formation of hospitalist solved these delays in care and patient throughput decades ago. However, if you told someone, a surgical patient requiring urgent surgery would need to wait in the ED for hours while a surgeon finished a scheduled operation, their endoscopy day, or completed rounds at another hospital, most people would see this as normal. This old-school method of surgical care has demonstrable issues: delays in care, worrisome outcomes, poor patient satisfaction, inefficient operating room utilization, and increased overall cost of care. How did we get to this model and more importantly why do we stick with it?

Becoming a Surgeon

All surgeons train under a residency program. These programs focus on the surgeon being the ultimate stake holder in their patient’s care. This reinforces the need for absolute attention to detail and avoidance of potentially deadly misses. During residency, this model is accomplished by a team of attendings, residents, and interns all splitting duties and responsibilities. Once done with training, surgeons who enter the private practice world, try to mimic this same model without the team and achieving the same results is very difficult for one person.

The community surgeon balances their private practice, including office hours, OR block time, endoscopy days, and personal life with their call responsibilities. Historically, surgeons were trained under the, “more work, the better” philosophy and relied on call days to build their elective practice. As the world has changed and insurers determined who patients can see, reimbursement shrank, and training programs limited hours attracting residents who desired more of a work life balance, being on call became much less desirable and much less lucrative. Surgeons began to push back and limit the call days they would take. Hospitals began to pay call stipends to make taking call more attractive. The catch with paying someone to take call is that it does not change all the factors that made taking call a problem in the first place. Call pay does not change the number of patients who need to be seen in the office or the number of elective cases scheduled during block time. It does not change priorities; “I am still a private surgeon and my practice, and my patients will always take priority over the hospital’s.”

Building Better Internal Medicine

Internists and hospital administrators fixed these issues with medicine in the 1990’s with the invention of the hospitalist service; internal medicine physicians dedicated to hospitalized patients. Patient care was not delayed nor jeopardized due to the spilt focus of running outpatient and inpatient practices and outcome improvements were immediately seen under this model. Efficiencies in testing, cost containment, and patient throughput emerged. It just makes sense to individualize care unique to hospitalized patients.

Time to Build a Better Surgeon

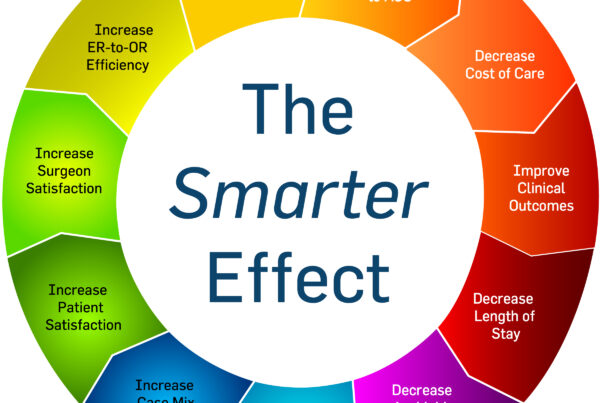

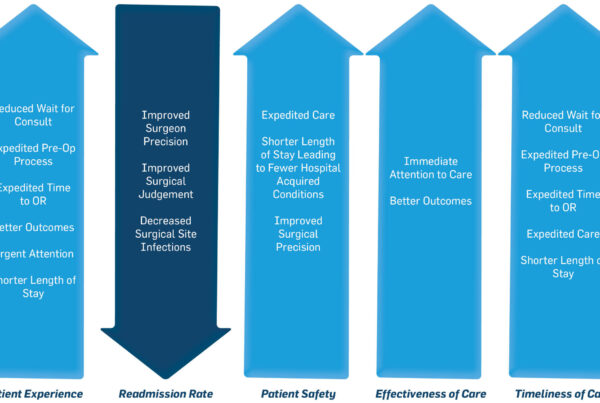

Surgicalists essentially address the same deficiencies in surgical care the hospitalists looked to improve in medical patients. A surgicalist is solely focused to the hospital and the patients who are admitted or who need urgent or emergent surgical evaluation and care. With a dedicated surgeon on call 24/7/365, consults are seen more rapidly, OR cases are done at the first available space, discharges are completed sooner, and most importantly, more cases are captured from the ED instead of being sent home to simply bounce back to the ED or follow up elsewhere. Under a surgicalist model not only do efficiencies and profit increase, but complications decrease. Multiple studies show, just like other specialties, when surgeons focus on one type of practice, their complication rates drop and outcomes improve.

Surgeons are competitive and it is common to not want to give up call out of fear of losing business. What happens after the institution of a surgicalist program is actually the opposite. By off-loading the burden of call, the community surgeon (whether employed by the hospital or in private practice) can focus more intently on his/her private patients. They have fewer canceled office days due to emergencies, they can schedule more cases without having to worry about urgent or emergent cases popping up, and they can build their practice without the risk of losing the little free time they have left. Surgicalists refer non-urgent cases back to the community surgeons bolstering their practices and simply removing the acute and unscheduled operations.

Change is difficult and often unwanted even though it is for the better. We no longer live in a world where ‘surgeon knows best’ – there is a better way. ED’s are busier than ever and a patient cannot occupy a room for hours waiting to be seen by the surgeon. Being a team player with ED colleagues is essential to improving efficiency at the gateway to the hospital. Patient satisfaction is a very important factor for hospitals to stay competitive and surveyed patients overwhelmingly prefer the surgicalist model of care. EMS providers prefer transporting to hospitals where they have confidence in the care their patients will receive. Most importantly after patient care, efficiency leads to revenue and revenue allows us to take better care of our patients. Surgicalists improve case capture, number of cases performed, and profit for health systems.

The smarter way to operate is here and it has been since the mid-2000’s. It is time we abandon the old model and upgrade to the model that has proven beneficial on all sides of the equation- improving patient care and outcomes, unburdening community surgeons, and optimizing hospital’s efficiency and profit.